|

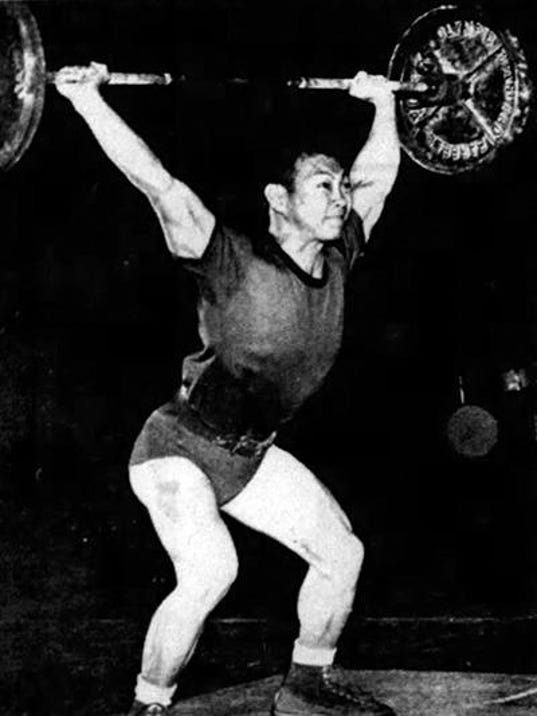

Former Weightlifter: Imahara’™s legacy like chapters in a bookBruce Brown, The Advertiser, July 4, 2017 There is a sense of history when you visit Imahara’s Botanical Garden in St. Francisville, as well as a sense of pride in celebrating a life well-lived. Walter Imahara was a champion weight lifter for SLI-USL in the 1950s and ’60s, a late arrival to the sport who learned quickly and used iron will and sharp focus to achieve greatness. And, to this day, he keeps nearly every trophy, plaque and award he’s ever received in the sport at his office at the Garden.  Walter Imahara was a member of the first championship weightlifting squad in 1957. (Photo: UL Lafayette Office of Communications and Marketing archival files / UL Office of Communications and Marketing archival files) MORE: Documentary to chronicle weightlifting’s heyday at UL He can also produce a notebook in which he carefully documented every meet he ever entered, with a chronicle of each performance and place. He began that notebook with his first meet, a meticulous examination of a process before he had any idea it would define half of his life. But Imahara describes weight lifting as a chapter in his life, saying simply, “That chapter closed, and I moved on.” He’s just as pleased to showcase the more than 150 Haikus carved into wood by his father, James Imahara, which adorn the walls of the room where he offers presentations to visitors. It is to his parents that the 54-acre sanctuary is dedicated. And, in an adjacent room, Imahara will proudly provide highlights of his family’s history through numerous photographs and timelines. It is a history interrupted by heartache, but one salvaged by triumph, of a Japanese-American family whose members kept the faith in their own inherent worth as well as in the nation that mistreated them. In the final analysis, Walter Imahara’s life is the great American success story. Unexpected upheaval When Japan staged its sneak attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, it plunged the United States into World War II. It also caused the relocation of some 122,000 Japanese living on the West Coast — 70 percent of them Japanese-American citizens — as authorities deemed their presence a security threat should Japan invade the U.S. Asian families living as much as 100 miles inland were sent to “relocation centers” — called concentration camps by those affected — to wait out the war. Names were replaced by numbers. Possessions were forfeited. The Imahara family — including eight children and a ninth on the way — was moved first within California and were kept for weeks in horse stalls until the next destination was determined. The couple and their children ended up in McGee, Ark. “We were there 3½ years.” said Imahara, James’s No. 1 son. “We were told we had to go there for our own protection. “As kids, we would play baseball, play games, have fun. And, every day, we would pledge allegiance to the flag.” Undaunted by the treatment of his family, James Imahara vowed to not only survive, but thrive, in his native land. When the war was over, the family moved south to Louisiana and education was stressed for every child as the path to success in America. “All of us received college degrees,” Imahara said. “There were four boys. We all served in the military and all came back home (alive). “We lived in a shack in Baton Rouge. My father worked two jobs (one as gardener at Afton Villa) to eke out a living. We finally found a home on Aug. 20, 1950.” The children converted from Buddhism to Christianity during that formative time. Imahara attended Istrouma High, largely unnoticed at a school enthralled with the exploits of football star Billy Cannon. Small and weighing 125 pounds, Imahara was not into athletics. “In 1955, Istrouma got some barbells, and I fooled around with them a little,” said Imahara, who initially went to LSU for further education. “It was too big,” he said. “There’s no way I’m going to get to the next class in 10 minutes. There were 100 people in a class. I was a nobody again.” Change of direction Imahara elected to attend SLI, and the move changed his future. “That was the beginning,” he said. “Going there was the turning point of my whole life.” In the fall of 1955, Imahara met Mike Stansbury, a weightlifting enthusiast who said Imahara had a similar build to world weightlifting champion Tommy Kono, another Japanese-American who had survived relocation camp life. “Mike said I had the same build for the squat position as Tommy, and that I should try lifting,” Imahara said. “It changed my life. Before, I had low self esteem, my grades were bad and I had no ambition. All that changed. “He was my mentor for the long journey. He gave me self confidence and self esteem on the platform. He taught me to never be afraid to try for a new record. “I wasn’t great, but I didn’t talk, and you were going to have to beat me on the platform.” The team worked out three times a week at the gym in Abbeville and represented the school in the NCAA, getting a supportive boost when Whitey Urban became athletic director. In his first meet, an AAU invitational in Arkansas in 1955, Imahara totaled 425 pounds (press, 130; snatch, 125; clean and jerk, 170), finishing second in bantam weight competition, and entered it in his notebook. By 1968, after he had finished college and was still competing, a 140-pound Imahara totaled 815 (press, 255; snatch, 240; clean and jerk, 320). Featherweight Imahara totaled 645 pounds, won first at 128 pounds and was All-American in leading SLI to the NCAA team title in 1957 in Lafayette. The 1959 NCAA was held in Pittsburgh, and Imahara triumphed again with a 695-pound total effort in featherweight action as SLI placed sixth. Another crown was his in 1960 in Maryland when Imahara had a 725-pound total en route to All-America and Best Lifter acclaim. The team finished fifth in scoring. “That was the beginning of my life in weightlifting, and Mike prepared me for the long journey,” said Imahara, who graduated in horticulture in 1960. “I received the first athletic letter at USL for weightlifting,” he said. “I was the first Japanese-American to graduate from USL. Dr. Arceneaux handed me my diploma and said I was their first Asian Cajun.” Imahara earned NCAA titles (1957, 59, 60), a Junior National crown (1960), Senior National titles in 1963, 64, 65, 66, 67 and 68, the 1967 Pan Am Games gold medal, Southern AAU (1956, 57, 58, 60, 64, 65, 66, 68), the Louisiana State crown in 1956, 58, 59, 64, 65, 66), the Southern USA in 1960 and 64 and was the National Masters champion from 1980-2005 before retiring from competition. In Masters action, he held 71 national records, 35 Pan American marks and 42 World Masters-Masters Games records. No athlete in USL history is more decorated. Remain calm Imahara joined the Army after graduation and continued competing. At officer candidate school, he found some of the same prejudice he encountered during World War II. But he remained calm. When a “6-foot Caucasian” told him to drop and give him 100 push-ups, Imahara did so with ease. He excelled at weightlifting competitions during his hitch, handling slights with his characteristic composure. But deployment in Germany near the site of the infamous Dachau Concentration Camp left him shaken. Now, 55 years later, he still can’t discuss that experience. From 1989-2008 Imahara served as IWF World Masters chairman, and was instrumental in anti-doping measures as well as using international referees and a code book of technical rules. Once out of the Army, Imahara migrated back to south Louisiana and became a successful landscape gardener, eventually with three locations in Baton Rouge. “I started out with a wheelbarrow, a shovel and a pickup truck, and ended up with three centers,” he said. “My father told me to buy land and build as you go. Get your retirement.” Now in his 80s, Imahara and wife Sumi enjoy the beauty of his Botanical Garden, carved out of rolling terrain in West Feliciana Parish that includes swamp land and hills, abandoned railroad tracks and native vegetation. He literally moved the earth to create a scale, mini-Mt. Fuji as one highlight, which looks down upon a series of nine ponds that feed into each other. He bought the land in 2003, and began the dream in 2009. Featured are some 3,000 azaleas, 25 varieties of crape myrtle, holly topiary groves, dogwoods, cypress, palms, magnolias and other plants, all trimmed to perfection in the Japanese horticulture tradition. There is the Mom and Pop Garden, as well as a Topii, a traditional Japanese gate that separates the physical and spiritual world, among the highlights. It is a special world created to honor a unique family. The Imaharas could have been bitter over their treatment in World War II, but they rose above their plight to live the American dream in spite of misguided Americans around them. And the diminutive Walter Imahara stands tall in that legacy. This story is part of an ongoing series at www.athleticnetwork.net, a website dedicated to preserving the history and traditions of almost 120 years of athletics at the University of Louisiana. Please email athleticnetwork@louisiana.edu for more information.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||