|

Baseball: Father, son – Papo Ramos’ kid Marco tries to make UL baseball teamTim Buckley, The Advertiser, Oct. 29, 2017 It is September, and classes are underway at UL. To the east, over the warm waters of the Caribbean, a deadly storm hits Dominica, then sets its sights on the next target. In Lafayette, Marco Ramos’ mind is immersed in a mission to accomplish what he could not a year earlier. The junior-college transfer is toiling, again, to make UL’s baseball team as a walk-on. In Puerto Rico, the horrible hurricane — they call her Maria — devastates the island. It strikes as a high-end Category 4, blowing gusts up over 200 miles per hour and leaving a still-ongoing crisis in its wake. Marco’s father Papo Ramos — a wildly popular brawler whose exploits hold a special place in Ragin’ Cajuns baseball lore — and his mother, the former Maria Christina Giron — an ex-UL volleyball player — survive a disaster that upends their lives and those of millions of Americans who call Puerto Rico home. Marco is conflicted, his head trying to stay locked in on making the team, his heart broken by what’s happened.

More: Maria grows stronger “My mom called me the day before (Maria hit),” Marco said a few weeks later. “She was like, ‘Marco, I don’t know when I’ll talk to you next. I don’t know when we’ll be in contact again. But I love you, and we’ll be fine here. We’ll stay where we are; there’s nowhere, really, to go.’ “We hung up the phone call, and I couldn’t really sleep that night. It was hard knowing I’m not going to be able to talk to my parents for at least a week.” Marco must keep his attention on school, and baseball; he knows there’d be nothing he could do from so far away. Yet, that’s easier said than done, especially as the hours of waiting to learn his family’s fate turn to days. “I was out here giving it my all; in the back of my head, I’m like, ‘I can’t call my mom and tell her what I did today,’” he said while standing near the outfield of Russo Park at M.L. “Tigue” Moore Field. “I didn’t even know what they were doing — if they had water, if they had food, if anybody’s trying to loot the house. “A bunch of things were going through my head, and I was just trying to stay focused and have confidence that God was watching over them and they’d be safe.” ‘WAITING FOR THAT PHONE CALL’By God’s grace, Papo (his given first name is Yariel) and his wife (they call her Tina) were safe. So was Marco’s sister Adriana, a former Norfolk State volleyball player who now works at a San Juan restaurant. But with power and communications down throughout most of the island, much time passed before Marco knew for sure. close

Early on, hospitals were closed, fuel was at a premium and food couldn’t be delivered to areas where homes were blown to bits and roads were washed out.

More than a month later, most of Puerto Rico still is without electricity, and will be for months; drinking water is tainted, and there’s no telling when some areas — especially rural ones — will return to normalcy. Related: Yes, this hurricane season has been worse than usual “I was just waiting for that phone call,” Marco said, “and finally my dad called me though a government line and told me my family was OK.” Papo Ramos — largely responsible for igniting UL’s decades-old baseball rivalry with South Alabama, and a man who once chased an opposing fan with a bat in hand — remains in Puerto Rico today. Employed in the investigations branch of the United States Department of Homeland Security, Papo currently is the acting deputy special agent in charge in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. He’s usually busy investigating everything from narcotics smuggling to human trafficking, money laundering and much more. But that changed after the hurricane arrived, prompting deviation from the usual core mission. “Since Hurricane Maria,” Papo said, “we’ve been, wow, dealing with a lot of humanitarian missions over here.”  Buy Photo Buy Photo

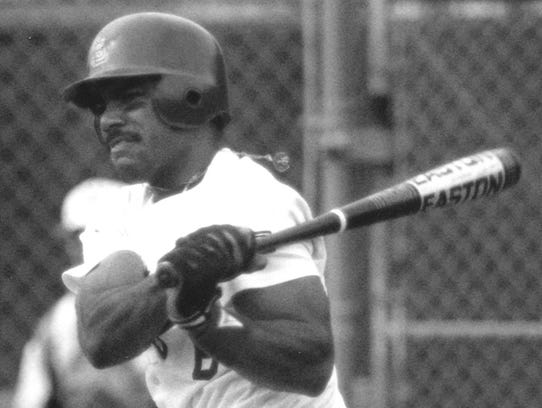

Former UL outfielder Papo Ramos was known for his power at the plate back in the day. (Photo: ADVERTISER FILE PHOTO) Before Maria hit, but after Hurricane Irma did extensive damage in the Virgin Islands and elsewhere just a few days earlier, Papo and Tina did what they could to help victims of that horrific storm. “Two of the most unselfish people I know,” said Jay Walker, UL’s longtime baseball play-by-play announcer. “They’re just wonderful, wonderful people.” And soon they were victims themselves. When Maria came, the tables were turned and Puerto Rico’s infrastructure was destroyed. “It ripped apart everything,” Papo said. As Maria hit with high winds that shook everything in sight, Papo — who doesn’t frighten easily — admits that even he shuddered. The house in which he and Tina stayed, and which Marco has known as home ever since he’s been in college — the one located in the Northeast coastal town of Luquillo, not far from Fajardo and about 30 miles from the capital city of San Juan — took a beating. “It was scary,” Papo said. “Water was coming in. “Thank God it was a cement-structure place. But a lot of people were not as fortunate as us. … The following day that you go outside and you see everything gone — it’s been tough.” Another view: Puerto Rico’s recovery needs Trump’s leadership One of Papo’s tasks in the storm’s immediate aftermath was to provide security so fuel could get to the many Puerto Rican gas stations that had none. With the supply severed and reserves drained, customers waited in line eight to 10 hours and were allowed to purchase only a capped amount. Tensions frequently ran high. “The truck drivers were scared,” Papo said, “so we started escorting the gasoline trucks. “It was crazy.” Papo — who has much of his side of the extended family still in Puerto Rico — has remained on the island to assist as it rebuilds, because that’s what law-enforcement types do. But his wife evacuated a week or so after Maria struck and relocated to Louisiana, where her relatives still live in the Opelousas area. She maintains the database for the special education program in a Virginia county school system, and can work remotely. But with Internet connectivity so unreliable in post-Maria Puerto Rico, Marco’s mother had little choice but to find alternate accommodations. Related: U.S. braces for potentially large numbers of Puerto Rico evacuees “She wants to see me play ball,” Marco said of his mother, who never got to watch one of his juco games, “and she was telling that if I make things happen and make the (UL) spring roster then she’s definitely staying for a long time.” Papo, however, couldn’t leave. “The bad guys are taking their chances right now while everybody is weak,” Marco said, “and he has got to be out there still stopping them as well as helping the people out.” ‘TIMING HASN’T BEEN PERFECT’Much like Puerto Rico’s future, Marco Ramos’ quest to play for the Cajuns comes with no guarantees. When his father worked out of Homeland Security headquarters in Washington, D.C., he played on a travel team and as a freshman at his Virginia high school. The requisite year-round commitment, however, started to take a toll. Marco, as his father tells it, sometimes wanted to fish on the weekends. One day, he approached Papo with some tough-to-take news.  Buy Photo Buy Photo

Marco Ramos, trying out for the UL baseball team, is a singles hitter who plays with passion. (Photo: SCOTT CLAUSE/THE ADVERTISER) “He told me … after his freshman year that he was going to quit baseball and start playing golf,’” Papo said. “I told him, ‘What? You want to be a Chi Chi Rodriguez? That’s the only good Puerto Rican I know that plays golf. But go right ahead, son. I’ll support you.’ It just broke my heart.” As it turns out, Marco’s interest in fairways and greens wasn’t the world’s worst thing. Papo even picked up the clubs and enjoyed some quality father-and-son time on the links. But he’s never been very good at the game — “I kept kicking the front leg every time I wanted to hit the ball” — and laughs about it now. Papo laughs a lot. With what’s happening at home, the only alternative is to cry. It was around the time of Marco’s baseball-to-golf defection that Papo was assigned to Mexico, where he worked at the U.S. Consulate General in Guadalajara. Marco’s high school there didn’t have a baseball team, but he wanted to play the sport again and joined a local team instead. “I saw a lot of good pitching — a lot of off-speed pitches, a lot of curve balls, change-ups. A lot of lefties,” he said. One of Marco’s teammates in Mexico was Papo, a right fielder for the Cajuns who decided to try out even though his career in the minor leagues had ended in 1993.  Buy Photo Buy Photo

Papo Ramos, shown here in front of centerfielder Wade Sholmire (36), took part in a brawl or two when he was a Cajuns baseball player. (Photo: ADVERTISER FILE PHOTO) “I had to get back in shape,” Papo said, “and we both made the team.” Prior to his senior year in high school, Marco — staying with a family friend — returned to Virginia and his old school there, Riverbend High in Fredericksburg. He made the baseball team, had some success and wound up at Seminole State College in Oklahoma. But the corner outfielder played sparingly at the juco, mostly pinch-hitting, and afterward NCAA Division I offers didn’t exactly pour in. “Marco has been playing behind players that have been drafted, and a lot of talent,” Papo said, “and for some reason the timing hasn’t been perfect to him. But he never quit.” It’s just not in him, much like backing down isn’t exactly in his old man. ‘THE BRAWL IN THE FALL’When he was at Seminole — yes, that same one — Papo’s team traveled to get games in the fall. On one trip, the club split and some played against UL (then called USL) while others played against McNeese State — coached at the time by current Cajuns coach Tony Robichaux. Robichaux remembers like it was yesterday his first full Papo Ramos experience. “I call it the brawl in the fall,” he said. Papo crouched a la Houston Astros Hall-of-Famer Jeff Bagwell when he hit, and that evidently started it all. “Ninety-nine-point-nine percent of the time, when you get those hitters that hit in the crouch,” Robichaux said, “we’re gonna bust up and in. So people would try to bust him a lot. And that’s what made him mad all the time.” McNeese’s pitcher was Shelby Shaw, later drafted by the Texas Rangers. Related: UL coach Robichaux to enter McNeese Sports Hall of Fame With Papo at the plate, Robichaux picks up the call: “(Shaw) goes up and in. Doesn’t hit him. Gets a little close. I think we get him out. … But he’s running down the line, basically cussing the pitcher out in Spanish. We assumed. The tone of it surely made it thataway.” Papo’s next at-bat? “We got up and in again, and we get behind in the count," Robichaux recalled. "So he does, like, a leg kick, and grunts, and he hits a 3-1 fastball (to) Shelby Shaw back up the middle. But it hits the pitching rubber, kind of flies up in the air. A single. “But he’s running down the line cursing. So Shelby picks over to first a couple times, and Kurt Heble (McNeese State’s first baseman) put a couple tough tags on him. … (Papo) got up and he punched Kurt Heble. And we fought.” Did they ever. When the last haymaker was thrown, and everyone calmed down, the two teams continued playing. Papo, however, was banished to the team bus, which was parked near the Cowboys ticket booth in right field. “On his way to the yellow canary, all the fans were hollering and stuff,” Robichaux said. “And that dude took his shirt, and, boy, I mean, he Hulked it.” Related: I’d be honored to have my kid throw down for Robichaux Robichaux, having stepped out of the seat behind his desk, imitates Papo ripping his shirt apart. “So he gets to the bus — I’ll never forget this — and all those windows are down, and he must have his hands on the two seats, and, I mean, he’s rocking that yellow canary, cussing in Spanish,” Robichaux said. “What’s so funny is the next day I pick the paper up — and he signs with USL.” So it wouldn’t be the last Robichaux sees of Papo Ramos, whom he wouldn’t have minded signing himself. Papo played for the Cajuns in 1991 and led them in home runs (16), RBI (46) and hits (82) in 1992. “You know what? I remember Robichaux,” Papo said. “You know why I remember Robichaux? Because I hit three home runs off (his team) in one game one day.” “That was the best game in my life. I saw the ball like a basketball coming down that plate.” Those were “crazy” times, Papo said. But they’re not nearly as loco as what’s happened in Puerto Rico, where Papo has a job he might never have gotten if he hadn’t been cut short in another of his wacky games. Coach Mike Boulanger’s rough-around-the-edges Cajuns were playing Nicholls State, and the opposing fans — as was so often was the case — were on Papo. Hard. Related: Recalling a special era of baseball He remembers several of them being Nicholls football players. “I think I was 0-for-3 … and the comments were getting to me,” he said. Then he heard something said about his mother. “So I ended up, after the third out, going to the dugout,” Papo said. “I picked up a bat. They said, ‘You’re not gonna hit right now; you already hit.’ “And I said, ‘I’m gonna do something else.’ And I hauled ass to the outfield fan area. I started chasing particularly one guy.” What unfolded sounds like quite the scene. “He kept jumping (over a short fence) back into the field,” Papo said. “When I would jump back to the field, he would jump outside of the field. So we did that for a while, and everybody, you know, piled on me. I didn’t get to get a good swing. “But I’m glad, because I don’t think I would be working for the Department of Homeland Security now.” Cue the laugh track. “That’s the stuff nobody can do now,” Papo said, “because you’d probably go to jail.” Nicholls fans. McNeese fans. Lamar fans. Thanks to hard-hit balls, barbs and brawls, Papo had a special relationship with each and all. But no brouhaha had longer-lasting implications than what went down with South Alabama. Column: Overall, Cajuns lacking bitter sports rivalries of yesteryear With the memories of so many a tad hazy some two-and-half-decades later, details on precisely what happened and when tend to differ a bit each time the tales are retold. But the bottom line in this one is that Jon Lieber, who went on to to pitch in the majors, hit Papo with a pitch during a 1991 NCAA Regional game. The bad blood spilled over, and when Lieber nailed Papo a second time in the same 1992 game — this time getting him in the ribs — Papo charged the mound. “That’s when hell broke loose,” he said. What Papo remembers most is the blood pouring from someone’s ear — whose, he cannot recall. “And that,” he said, laughing yet again, “was the first game my parents had seen me play in college ball.” It’s also the day, play-by-play man Walker wrote, when “a rivalry was born.” From snap-glove catches to his brash willingness to throw down whenever and wherever, a Cajun legend has withstood the test of time. “I guess for some reason they used to see me as a very cocky player,” Papo said. “(But) it was never my intention, you know, to portray that in a very negative way. It was just the way I played the game. “But with South Alabama, for some reason, every time I would do good I would blow kisses to the fans — because I (knew) that was gonna get ’em crazy.” ‘DAD, I KNOW YOU WERE HUGE’Marco Ramos has heard the stories. “He’d tell me about the little fights he got in, the South Al fight,” Marco said. “He wasn’t afraid of it, that’s for sure — especially the one at Nicholls, when he took the bat into the stands when people were talking crap to him. That made me laugh.” So Marco can chuckle too. “He always tries to make me feel better — you know, ‘I wasn’t as big as you think I was,’” Marco said. Papo’s son, though, doesn’t buy it, telling him, “‘Dad, I know you were huge. Don’t make me feel bad.’” Marco could have pursued his bachelor’s degree just about anywhere. But he wanted to play at UL, even if it meant having to ask for a tryout.  Buy Photo Buy Photo

Marco Ramos tried to land a spot on the UL roster last season, didn’t make it and is trying again this year. (Photo: SCOTT CLAUSE/THE ADVERTISER) So now — he had to have sensed it would happen — it seems every time he turns at The Tigue someone brings up his father. “When I get introduced to these old-timers, especially — they’re the true fans — they always tell me, ‘Can’t wait to see you out there. Your dad was a stud. He’s one of the best,’” Marco said. “At first, yeah, I was like, ‘Man, I’ve got a lot to live up to.’ But that was too much pressure. … So I’m using my dad’s legacy to motivate me right now. But I’m not trying to ‘follow his footsteps,’ because I will never be just like him.” Papo pulls for Marco to get his chance, but doesn’t want his son traveling the exact same road either. With a lifetime’s worth of wisdom gained, the father knows now he might have gotten carried away a time or two. “He has that in him,” Papo said. He’s accordingly warned his boy against ever getting too upset, telling him, “‘Marco, you cannot do this nowadays. … Those are old days. You cannot react that way. You’ve got to think. You want to end up with a good job when you finish school. … If you do something crazy, it will affect you the rest of your life.’” “But,” Papo hastens to add, “believe me, he has it.’ ” So although chunks of the elder are layered throughout the younger, they’re still two of a kind. “So I kind of want to make my own path,” Marco said. “But it does motivate me, knowing a lot of people know him and a lot of people know me — and I haven’t even played a spring here yet.” ‘I DIDN’T WANT TO GIVE UP ON IT’Papo knows well just how hard that first fall — last fall — was for Marco at UL. It was an autumn to forget. Robichaux cut him, and it still stings. “So I kind of stopped for about two months,” Marco said. “I didn’t swing the bat.” Then the itch returned. “(I) went to the cages one day and started swinging again,” Marco said, “and I said, you, know, I can’t leave it like that. “‘I want them to tell me in front of my face that baseball is over, (so) I can to sleep at night saying I left my heart out on the field.’ “So,” he added, “that’s what I’m doing right now.” After last season, when his players scattered, some getting as far from The Tigue as they could, Robichaux would leave his office at night and see Marco working on his hitting. Related: One shining moment? Not for Robichaux’s Cajuns "You know what?” Papo said. “He’s resilient. … He never took ‘no’ for an answer.” How could he? “I didn’t want to give up on it,” Marco, “not knowing — you know, maybe I could have had a chance the next year.” Papo encouraged Marco to stick with it and give it another shot, telling him, “‘It’s gonna click. I don’t know when, son, but it’s gonna click, I guarantee you.’ “I told him, ‘Marco, if you hit you play anywhere. So you basically need to become an artist at home plate.’” ‘BEAUTIFUL-HEARTED PEOPLE’Papo and Tina were married at home plate of The Tigue in 1992, and figured they were about to embark on a long career in pro ball. But Papo stopped playing a short time later when, much to his surprise, he was told his time was up. Selected by the San Francisco Giants in the 1992 Major League Draft’s 23rd round, he hit .306 with 11 doubles and a couple homers in 66 games as a rookie for the then-Everett (Wash.) Giants of the short-season Class A Northwest League. Papo was hitting .308 through just three games the next year for Clinton (Iowa) of the Class A Midwest League when he was released. Tina was pregnant at the time with Adriana and, without insurance anymore, times were tough. The two had met at UL, after Papo first got to know her father at church. As Papo shares the story, he sang in the choir in a Spanish-language Catholic Mass on campus and after a service one day he was telling someone about needing help with one particular subject. Tina’s father, a man of Guatemalan descent who played guitar at church, heard him and told Papo to call his daughter for assistance. They met at the library. “Forget it,” Papo said, the laughs starting to build again. “From there on, I don’t think we even talked about my problem in that specific class.” Related: Remembering the Tigue’s Vic The Peanut Man Out of the minors less than two seasons after getting in, Papo — three courses shy of graduating — and Tina soon returned to the familiarity of Acadiana area. “Thank God I had a lot of beautiful-hearted people that were fans,” he said. Someone helped him get a carpentry job, even though he knew nothing about the craft. He briefly worked at Walmart, for FedEx and — the best job of the bunch — in the oil fields. But, wanting more, Papo returned to school and applied for federal jobs, first landing one in 1996 as a U.S. Customs inspector in Puerto Rico. That kick-started a career that would later take him to the D.C. area as an ICE special agent, to Mexico and finally back to Puerto Rico. ‘HE PUSHES PEOPLE’Now Marco is majoring in criminal justice, with plans to join what’s become the family business. (Papo’s younger brother, Alberto, played for UL under Robichaux in 2002 and is a police officer in Florida.) First, though, Marco has this team he’s trying to make. As the Cajuns head into their fall-ending best-of-three intrasquad starting Monday, the odds seem stacked against him. Twenty-seven UL roster spots are allotted to scholarship players, and three of the remaining eight are tagged for returnees, leaving five spots for a couple dozen or so hopefuls, Marco among them. “He’s put in a lot of time and a lot of hard work,” Robichaux said, “and he has gotten better from last year to this year. “The biggest challenge for us, always in these situations, is (roster limitations).” Related: UL baseball unveils challenging 2018 schedule Marco, a left-handed singles hitter who plays with passion, is on the bubble. If he makes it, it largely will be because of attitude and approach. “He’s what I call ‘a pusher,’” Robichaux said. “He pushes people.” Guys like that are great in the clubhouse. But for a team short on experienced pitching, there isn’t necessarily room for them all. Family ties — the Ramos story — make the call that much tougher. “Because it’s a good story,” Robichaux said. “He checks a lot of boxes. For this sport, you want pushers. You want good stories. You want guys that have worked hard. You want guys that (it) means a lot to them.” A decision will be made sometime next month. “I think everybody will tell you: The guy plays hard, runs hard every day,” Robichaux said. “You can see he really wants this, and that makes it so much harder on us. You don’t want it to become ‘Rudy,’ but the team starts to also want a guy like that.” Whatever happens, Papo suggested, Marco will be at peace with it. “He said, ‘Papi, I went all out. I’m satisfied now,’” Papo said. A year ago, he was not. Related: Will atmosphere at The Tigue change with renovations? “It hit me hard,” Marco said, “because I’ve been playing ball since I was 4 … “And for them to tell me I wasn’t gonna make it — it’s been a dream for me to come to UL to play here, after my dad and my uncle. And I just want to make a dream come true. “And when somebody tells you that you can’t do it, it hurts. But they gave me the opportunity again. They didn’t tell me, ‘You’re gone forever.’ … You’ve just got to give me the opportunity, and I’m going after it.” The time between tryouts was trying, but Marco — hardened by his family move to Mexico — did not cave. “It hurt,” he said. “Especially people asking me, ‘Why aren’t you out there?’ “I kind of have to explain to them. Sometimes people want to know too much. But I’m the kind of person (who thinks), ‘They deserve to know.’ So I told them. But I told them I’ll be back as well.” He stuck to his word. As Marco waits now for word from Robichaux and the Cajuns, he does so with a feeling many back on Papo’s island know all too well. A sense, that is, of uncertainty. “Puerto Rico definitely is a different place now,” Marco Ramos said. “It’s not what I left it.” UL BASEBALLWHAT: ‘Fall World Series;’ best-of-three intrasquad series WHEN: 6 p.m. Monday, 3 p.m. Tuesday and (if necessary) 6 p.m. Wednesday WHERE: Russo Park at M.L. "Tigue" Moore Field ADMISSION: Free, clear-bag policy in effect, no outside food or beverages allowed, concessions will be sold insid Click here for video. Outfielder Marco Ramos is making a bid to join the Ragin’ Cajuns. Footnote by Dr. Ed Dugas. Marco’s mother, one of our proud HPE graduates, was also a Ragin’ Cajun athlete. Marie Giron Ramos was a member of the USL Volleyball 1987-91. Please click here for the 1991 Volleyball photo gallery.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||